This question motivates Resurrecting the Sublime, an ongoing collaboration between artist Dr. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, smell researcher and artist Sissel Tolaas, and an interdisciplinary team of researchers and engineers from the biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks, led by Creative Director Dr. Christina Agapakis, with the support of IFF Inc. In a series of immersive installations, the first in the exhibition La Fabrique du Vivant at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (opening 18 February 2019), the project allows us to smell extinct flowers, lost due to colonial activity.

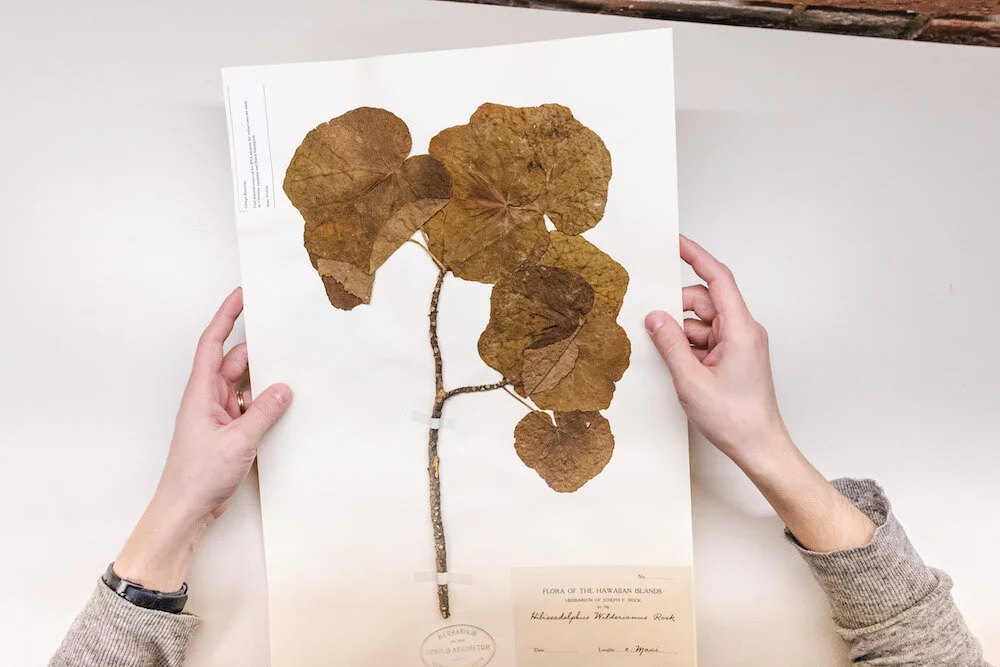

Using tiny amounts of DNA extracted from specimens of three flowers stored at Harvard University’s Herbaria, the Ginkgo team used synthetic biology to predict and resynthesize gene sequences that might encode for fragrance-producing enzymes. Using Ginkgo’s findings, Sissel Tolaas used her expertise to reconstruct the flowers’ smells in her lab, using identical or comparative smell molecules.

The Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock, or Maui hau kuahiwi in Hawaiian, was indigenous to ancient lava fields on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakalā, on Maui, Hawaii. Its forest habitat was decimated by colonial cattle ranching, and the final tree was found dying in 1912. The Orbexilum stipulatum, or Falls-of-the-Ohio Scurfpea, was last seen in 1881 on Rock Island in the Ohio River, near Louisville, Kentucky, before US Dam No. 41 finally flooded its habitat in the 1920s. The ‘Leucadendron grandiflorum (Salisb.) R. Br.’, the Wynberg Conebush has a more complex story, which we are still uncovering. It was last described in London in a collector’s garden in 1805; its habitat on Wynberg Hill, in the shadow of Table Mountain, Cape Town, South Africa, was already lost to colonial vineyards. This flower may prove to be completely lost: the project is bringing to light that specimens around the world may historically have been incorrectly identified.

While we can use technology to reach back into the past and learn which smell molecules the flowers may have produced, the amounts of each are also lost. In installations designed by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, fragments of each flower’s smell diffuse and mix, introducing contingency: there is no exact smell. The lost landscape is reduced to its geology and the flower’s smell: the human connects the two, and in contrast to a natural history museum, the human becomes the specimen on view.

Using genetic engineering to resurrect the smell of extinct flowers—so that humans may again experience something we have destroyed—is awesome and perhaps terrifying. This dizzying feeling evokes the sublime, an “expression of the unknowable”, an aesthetic state encouraging contemplation of humans’ position amidst the immensity of nature.

This is not de-extinction. Instead, biotechnology, smell, and reconstructed landscapes allow us to once again experience a flower blooming on a forested volcanic slope, in the shadow of a mountain, or on a wild river bank, revealing the interplay of species and places that no longer exist. Resurrecting the Sublime asks us to contemplate our actions, and potentially change them for the future.

Exhibitions

AI: More than Human

Fernán Gómez Centro Cultural

Madrid, Spain

July 22, 2021 – January 9, 2022How Will We Live Together?

Venice Architecture Biennale

Venice, Italy

May 22 2021 – November 21, 2021AI: More than Human

World Museum

Liverpool, UK

January 1, 2021 – June 1, 2021Being Human

Wellcome Collection

London, UK

September 5, 2019 – 2029Survival of the Fittest

Kunstpalais

Erlangen, Germany

February 28, 2020 - September 6, 2020Radical Botany

Eden Project

Cornwall, UK

February 15, 2019 – May 17, 2020Apocalypse - End without End

Natural History Museum

Bern, Switzerland

February 22, 2020 - December 31, 2020Polarities: Psychology and Politics of Being Ecological

MU

Eindhoven, Netherlands

November 29, 2019 - March 1, 2020Designs for Different Futures

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia, USA

October 21, 2019 – March 8, 2020AI: More Than Human

Groninger Forum

Groningen, NL

December, 2019 – May, 2020Better Nature

Vitra Design Gallery

Weil am Rhein, Germany

July 19, 2019 – November 24, 2019Nature—Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

New York, USA

May 10, 2019 – January 20, 2020Nature—Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial

Cube design museum

Kerkrade, Netherlands

May 10, 2019 – January 20, 2020OK CyberArts 2019 - Prix Ars Electronica Exhibition

Offenes Kulturhaus (OK), OÖ Kulturquartier

Linz, Austria

September 5, 2019 – September 15, 2019Resurrecting the Sublime

Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne

Saint-Étienne, France

March 21, 2019 – April 22, 2019La Fabrique du Vivant

Centre Pompidou,

Paris, France

February 18, 2019 – April 15, 2019Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival

The XXII Triennale di Milano

Milan, Italy

March 1, 2019 – September 1, 2019AI: More Than Human

Barbican Centre

London, UK

May 16, 2019 – August 26, 2019

Awards

Honorary mention, Prix Ars Electronica Artificial Intelligence & Life Art Prize 2019

Resurrection of the Year, Xconomy Awards 2019

Lumen Prize Rapaport Award for Women in Art & Tech, 2019

Selected press

Popular Mechanics: ( April 2019) “You Can Now Smell a Flower That Went Extinct a Century Ago”

The Pulse WHYY: (October 2019) “Between Life and Death”

Scientific American: (February 2019) "Fragrant Genes of Extinct Flowers Have Been Brought Back to Life"